The request is clear: listen to the territories, defend the water, respect the collective rights, let them be and decide, recognize their existence, their way of living and thinking, and, above all, understand that with lithium batteries there may be cars and cell phones, but without water there will be no one left to use or drive them.

Flavia asks us to get her message to Europe. Or at least, to break with the pattern where one (supposedly superior) alternative (the mainstream imposed by the Global North) diminishes, intrudes, displaces and/or eliminates other alternative ways of understanding the world and, therefore, of relating to nature (that is, to ourselves).

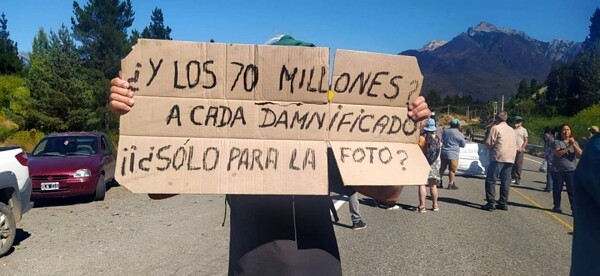

Flavia's voice travels along routes of salt and wind, but it points to the heart of the global debate on the ecological transition. In Argentina, the people, fortunately, and as a reaction to so many crises, know how to create resistances.

As for the first issue, the women of Susques, Flavia tells us—who, as we have already said, suffer the consequences of mining that has already penetrated for 10 years—manifest that it is no longer safe to go out at night, because there are many drunken and violent men walking on the street. That phrase summarizes the horizon they fear in the Salinas: an exhausted territory, a life fenced in by dust and thirst.

“We don't eat batteries,” Flavia tells us when we interview her at the refuge of Santuario de 3 pozos, at the entrance to the Salinas, where for a small amount of money (2 euros) they offer a tourist guide service where they tell us how the salar works and how the communities use its salt.

When the first drillers arrived in the area in 2009, the communities did not know what lithium was. “We don't eat batteries.” Perhaps that is the deepest message that the Salinas return to us: that the ecological transition will not be just if it is built on thirsty territories; that if the 'green' transition needs empty territories, fractured communities and salars without water, then it is neither a transition nor green, it is simply another form of extractivism, this time in the name of the climate; that there will be no possible world if we continue to silence voices that could help us imagine others; and that Pachamama, when she speaks in silence, is telling us that we still have time.

The Kachi Yupi Protocol, “Huellas de Sal” (Traces of Salt), formalizes the right to free, prior and informed consultation, and requires that any assessment and information be communicated in clear, non-technocratic language, in accordance with the deliberative practices of the basin. What is the point of a green transition that demands sacrificing entire territories in the name of a future to which these peoples will not even be able to access?

Flavia tells us about Susques, a community about 66 km uphill from where we are, one of the first towns in the Puna where lithium extraction advanced. The lithium that feeds electromobility is extracted from territories like this one, where water is scarce and democracy is fragile. We have to open up to new ways of thinking and understanding the world: only then will new solutions arrive.

The bond that Flavia has with the Salinas is also intimate and spiritual. “The Salinas are part of the family, and that's why we say that if they touch them, it's as if they were touching a mother,” she says. “And that breaks the community,” she explains.

However, in 2023, after the constitutional reform promoted by the governor of Jujuy, the rights of indigenous peoples were weakened. The protests were repressed and many communities were divided. “We saw that the salar was starting to sink, that fresh water was coming out mixed with brine.” There, Flavia tells us, “there is no drinking water during the day and the animals are born deformed.”

Flavia knows this. Her refined marketing artifacts know how to penetrate the communities. Although with limited connectivity and the Internet—since 4G is only accessible in certain parts of the road—the communities also receive (and especially since we live in this digital age) the constructs of progress, work, social ascent, success. “They tell us we are the lithium triangle and that's why we are going to be rich.” Objects that in the logic of colonial capitalism represent “having made it.” A car, a cement house, new clothes, jewelry, a better cell phone. But without water there is no life.

The help has to come from Europe, where the decisions about lithium are made. “There are human rights organizations there that can listen to us.” And because spreading the word is a political act. Here we are, trying to make her voice resonate in all possible spaces. At the end of the day, the question is not who will own the lithium, but what world we continue to feed when we believe that technology alone will save us.

Flavia knows. Her refined marketing artifacts know how to penetrate the communities. “They tell us that progress comes with trucks and machines, but what they bring is inequality. If my neighbor suffers, I cannot be calm.” Practices that did not exist before have appeared, and in particular, from a gender perspective, alcoholism and prostitution. In Susques, the promise of development turned into dependence. Before, no one had more than anyone else. Now some buy cars, others nothing. Objects that in the logic of colonial capitalism represent “having made it.”

A car, a cement house, new clothes, jewelry, a better cell phone. But without water there is no life.

The help has to come from Europe, where the decisions about lithium are made. “There are human rights organizations there that can listen to us.” And because spreading the word is a political act. Here we are, trying to make her voice resonate in all possible spaces. At the end of the day, the question is not who will own the lithium, but what world we continue to feed when we believe that technology alone will save us.