The women protesters know what a roadblock entails, but with so many doors closed in their faces, they regain the impact of such a measure, even if it is not massive. This could be because work continues alongside the firefighting, or because it is still not possible to unite the forces of all sectors fighting together to take to the streets.

Direct action is a form of resistance against the fire and its consequences. A few kilometers away, the fire remains active in Epuyén and Cholila. The forecast predicts high temperatures. Planes and helicopters fly over the area. Along National Route 40, pickup trucks with totems, hoses, water pumps, and donations for the affected areas circulate.

The reality of active wildfires brings with it combat, solidarity, anguish, and the need to highlight the state's neglect in the face of the advancing fire.

The women stress the urgency of denouncing that the funds allocated for the reconstruction of their homes never arrived. Despite repeated presentations and actions, they have found no solution or response to the lack of shelter for a year.

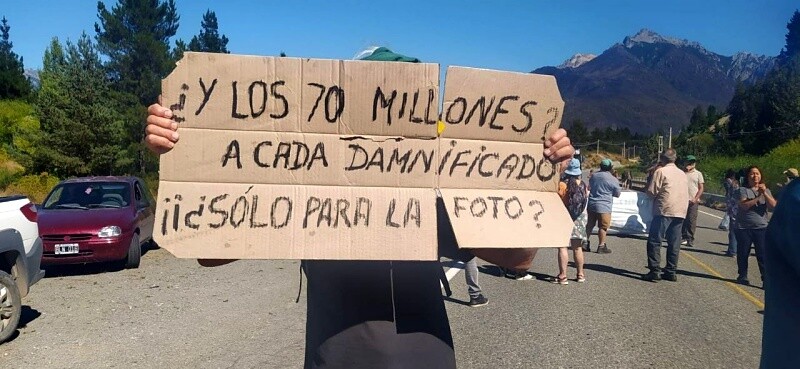

The women talk and are aware that this benefits the rulers who deny them resources, as a sign on the roadblock reads: "And the 70 million for each victim?". They stop to hug the protesters, smiling for photos among applause.

The roadblock is lifted for a few minutes, and they continue on their way. It is not easy to block a road; they give each other strength and try to lift their spirits. "The burned lands will not be stolen!" the protesters chant between car horns and applause during a roadblock.

They also discuss the fires in Chile's Biobío region, the lack of water or long queues for it in some neighborhoods, and bring into the conversation the alert over the glaciers and the labor reform planned for February, while everything is on fire.

Behind the solidarity that the media romanticizes, there is a collective learning process, a mix of resignation and popular empowerment: year after year, they have formed work teams to fight the fire with their own resources, facing a reality that repeats every summer.

This solidarity is somewhat reinforced when the roadblock is lifted for a few minutes, and those passing by applaud, raise their fists, or honk in support. In the background, burned mountains are visible, a landscape of loss and resistance. When it ends, there is more applause and laughter over their results.

Two women discuss the situation in Cholila, while traffic resumes, and support continues with honks. Some women stay on the shoulder even though they support the action. "Will solidarity always save us?" they wonder, as they name the political responsible for the defunding, abandonment, and lack of public policies for firefighting resources, let alone for housing reconstruction.

Nor is it spoken of that their bodies are exhausted, or that the environmental damage and losses are proportional to the damage to the mental health of those living in the Andean Region.

After the adrenaline of summer comes the harshness of winter, and there were neighbors who faced it in tents because they did not receive a single penny of the funds announced for them. They move away from the road for a small assembly. There is an urgent need to act so that the same thing does not happen this year. Bodies that, in addition to the fires, also withstand state and para-state criminalization, as seen a year earlier at the 12th Police Station in El Bolsón. They also condemn that the discourse of Ignacio Torres and the government of La Libertad Avanza is only one of criminalization against the Mapuche communities.

Very few of the outraged appeal to freedom of circulation, either in a hurry to escape the reality or because they do not feel part of those who defend the land in the face of a catastrophe like the one currently occurring. "Neighbor, tourist, do not be indifferent, they are setting us on fire in the face of the people," continue the chants of the protesters, as the agreed-upon time to hold the action runs out.

Since the interface fires began in 2021 (Cuesta del Ternero in Río Negro and Las Golondrinas in Chubut), they have been warning about the lack of maintenance in the electrical wiring, which constantly causes house fires. On the other hand, they alerted to the problem of abandoned pine forests—something that is now so talked about but is not a concern for the State or its institutions—desertification, drought, and the loss of native life cycles, which is a reality for Northern Patagonia.

In the assembly, it was decided on an intermittent roadblock so as not to affect traffic during the firefighting. Around noon, so that those passing by would know that the fire and the alert continue, and that the victims are still seeking answers and resources. They speak of the need to problematize and politicize that solidarity, instead of romanticizing it.

The Assembly of Affected Women of Epuyén in the 2025 fires, along with more neighbors, environmental and social organizations of the Andean Region, carried out an intermittent roadblock this Saturday, January 24th, at the height of the Río de La Mina bridge, on National Route 40, in the province of Chubut.