In Argentina, there is an ongoing debate about lowering the age of criminal responsibility for adolescents. Official statistics indicate a decrease in youth crime over the past 15 years, which contradicts the arguments of those advocating for stricter laws.

Sociologist Ana Laura López, a member of the 'Space of Relatives and Friends of Luciano Arruga', refutes the three main myths used to justify lowering the age of criminal responsibility: that youth are committing more crimes, that the number of crimes is high, and that they are especially serious.

According to official statistics, the youth crime rate has been steadily declining for the last 15 years. For instance, in the Province of Buenos Aires, 26,026 cases were reported in 2017, compared to 22,687 in 2024. This demonstrates a decrease in the crime rate among adolescents.

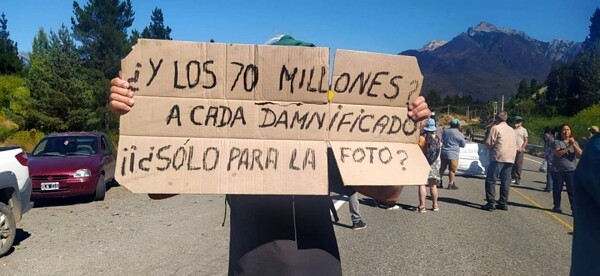

Despite these figures, the government is pushing to amend the penal code and lower the age of criminal responsibility to 14 (after a failed attempt to lower it to 13). Critics argue that this will lead judges to order more detentions in 'Socio-educational Centers for Juvenile Criminal Responsibility', which are, in practice, prisons as they lack any educational or reintegration programs.

'For the lives of adolescents, this implies a state intervention with persecutory purposes,' asserts López. 'This clearly indicates that it is a punitive detention.'

She also notes that these measures primarily target poor and racialized populations. 'The state, which was absent to guarantee their rights, now appears as a threat,' she says. 'The trajectories of many people, marked by abandonment, find persecution and punishment instead of care from the system.'

More punitive stances, including that of the Minister of Security, Patricia Bullrich, argue that adolescence is dangerous and must be regulated and controlled by a system of incarceration. However, data shows that adolescents commit only 2% of all crimes in the Province of Buenos Aires and less than 1% of serious crimes.

These centers employ penitentiary techniques involving humiliation, rights-violating searches, and a ban on personal belongings. Even the architecture is designed for hostility, featuring vandal-proof toilets and concrete beds.

Ana Laura López insists on calling things by their name: 'we should call them what they are: juvenile prisons.'

She offers the following advice to adolescents:

'Do not confront the security forces. Stay calm. The police will use any excuse to justify their violence. Try to stay with others. Shout your full name so that someone has a record of your detention. You have the right to demand that an adult be informed of your detention. Inform them immediately that you are being detained. Legally, they cannot detain you without cause; if they do, you have the right to know why. They can only detain you if they catch you committing a crime or have evidence of a crime that they must inform you of at the time.'

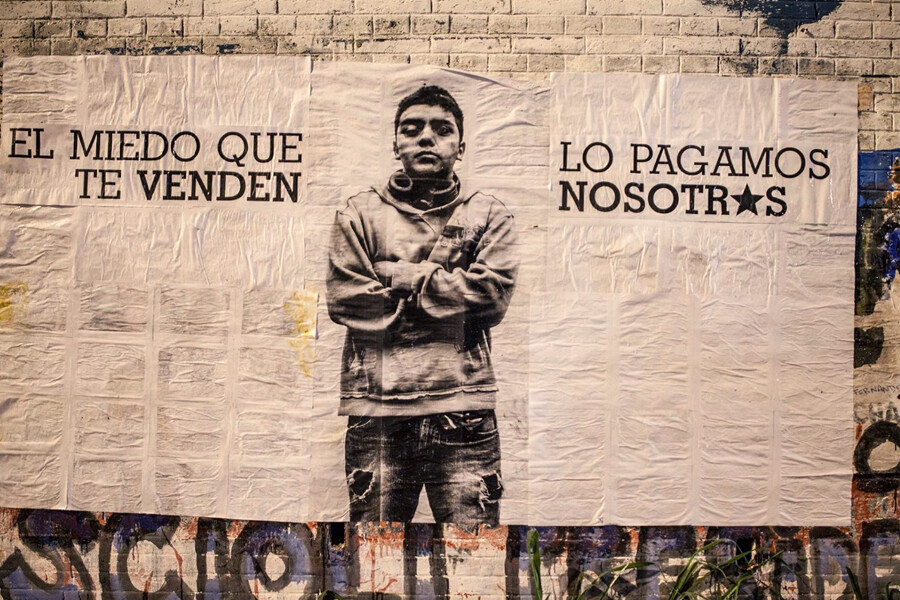

'The fear they sell to you, we pay for it,' reads a public intervention graphic.