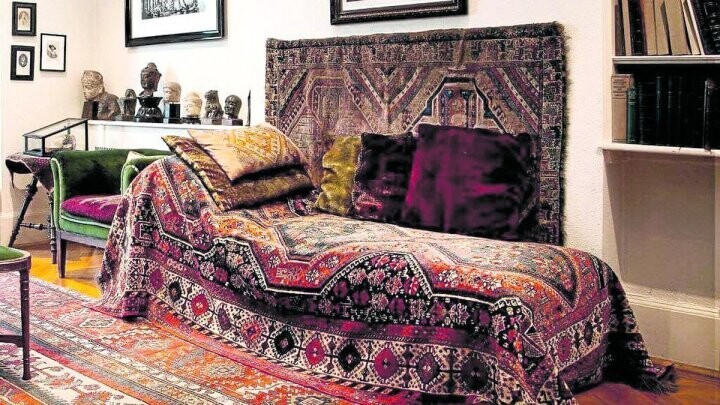

The impoverishment of social bonds paves the way for artificial intelligence to present itself as a 'therapeutic alternative': it offers companionship without conflict, listening without discomfort, and a complacent mirror that never challenges. A patient in Buenos Aires is not the same as one in Tokyo; grief caused by unemployment is not the same as that caused by a breakup. Chatbots, however, pathologize daily life, homogenize diagnoses, and turn intimacy into a commodity for tech companies, transforming the most singular aspects of subjectivity into exploitable data. Neoliberalism: an economic and cultural system. The rise of AI as 'therapy' does not herald an emancipatory future, but is a symptom of the deep crisis in public mental health: a lack of professionals, high costs in private care, the precariousness of life, and a system that pushes individuals to resolve in solitude what is a product of social relations. The effect is twofold: on the one hand, the human experience is trivialized (everything is explained by 'anxiety,' 'depression,' or 'productivity failure'); on the other, social conflict—precariousness, loneliness, neoliberal demands—is privatized, as if reprogramming the individual's mood were enough to solve collective causes. From psychoanalytic practice, we know that the symptom is a singular formation that points to history, culture, and the body. Algorithmic speed tends to homogenize: it diagnoses, it normalizes. The use of artificial intelligence in a therapeutic key is also a political and symbolic phenomenon that deserves analysis: what is understood by discomfort, who has the right to name it, and what relations are replaced or distorted when the human encounter is substituted by a conversation with a device that does not feel. By Rosa D'Alesio, for La Izquierda Diario. To speak, to be heard, and the place of the other The core of psychoanalysis is not the immediate answer or the use of empathetic phrases; it is the play of words within a framework that allows for transference: the construction of a singular bond, with its own timing, limits, and shared history. What social relations do we need to transform? Biases, dependency, and the illusion of impartiality Language models do not start from an ontological neutrality. The risk is clear: to naturalize the idea that suffering can be 'treated' by an algorithm while the state absolves itself. This scenario is sustained by neoliberal policies that weakened the public sphere and, at the same time, imposed a culture of individualism, personal success, and narcissism, where the other appears as a threat before a possibility of encounter. But in reality, they reinforce the logic of isolation and self-performativity imposed by capitalism, further emptying the experience of the word and the human bond. To care for the word, to defend mental health The replacement of the human word by chatbots is not a neutral technological advance: it is the crudest expression of a system that turns even intimate suffering into merchandise. In the face of the neoliberal colonization of intimacy, the task is to preserve the word as a human territory irreducible to algorithmic logic and to defend mental health as a collective right, by financing a public network that prevents therapy from being a luxury. But what is at stake is much more serious: it is not about quick advice, but about replacing the human bond with a device that does not listen, feel, or contain. In that framework, analytical listening—that presence that notes hesitations, silences, breaths, gestures—is not a mere technique; it is what enables the work with the unconscious, the analysis of repetitions and primal scenes nested in symptoms. Chatbots, no matter how empathetic they may seem, do not offer that place. They do not grasp the tonality of silence or the intervention that can give meaning to the drives. In doing so, they contribute to a new form of managing discomfort that avoids the political question: what social conditions produce suffering? This defense transcends a professional demand to become a political act: to prevent intimate life from being reduced to raw material and collective suffering from being cut with instant solutions that, in the end, do nothing more than naturalize the precariousness that gave rise to them. The limits of the couch To defend the word against the algorithm is a political struggle: it is about preventing mental health from being subordinated to both state adjustments and the logic of Silicon Valley. In this sense, in the face of the commercialization of health, the answer does not lie in individual adaptation to hegemonic models, but in building networks of solidarity that, in their own functioning, challenge the subordination of life to capital. As someone heard in their testimony, 'The best therapist I've had, without a doubt, has been ChatGPT': anecdotes like this speak of a real demand—immediacy, availability, affect without judgment—but they also show the limits of the recourse when it is supposed to replace a cure that requires word, transference, and an ethics of setting. Pathologization of daily life: from unease to a quick label There is a social risk that runs through this technology: the tendency to transform complex life experiences—grief, loneliness, unemployment, economic or political crises—into problems to be diagnosed and, moreover, solved in a chat. Daily conversation suffers when every discomfort must be translated into rapid clinical terms or simplistic recipes. They have no body, history, or sustained attention to the density of the other. They feed on historical and cultural data that also contain prejudices, stereotypes, and gaps. When speaking of traumas, sexual doubts, phobias, medical decisions, or suicidal ideation, it is not just about sensitive content: it is about intimate life in a state of vulnerability. This data is political: it is not the same to heal in a public or private framework, with remunerated and regulated professionals, as to 'heal' on a platform whose logic prioritizes retention, metrics, and profit. Confidentiality and professional responsibility are not formalities: they are conditions for the word to be able to say what hurts without being exposed to external uses. What an algorithm cannot replace: culture, setting, and singularity Clinical practice is based on knowledge that is not reducible to probabilistic responses: the reading of non-verbal language, the management of time and setting, and cultural contextualization. More and more people are using AI as a psychologist because it is fast, free, and always 'available.' These elements allow for a situated interpretation that takes into account the biography, tradition, social practices, and material living conditions. By reproducing them, chatbots not only replicate biases: they amplify and massively distribute them. While human beings, in their singularity, confront diverse biases in multiple exchanges, a standardized algorithm can propagate a single bias that runs through the entire population. This symbolic uniformity has a deeply conservative effect: it reduces the plurality of discourse and homogenizes ways of feeling. Privacy, interests, and the commercialization of intimacy Unlike the professional who works within ethical frameworks, interactions with chatbots are often recorded, analyzed, and monetized.